Simulating your CPU

Have you ever wondered what goes on in your computer when it runs something? No? Then what else are you here for - get outta here.

This project was done as part of COMP30023 Computer Systems in 2023. One of, if not my favorite subjects that I’ve ever taken. I’m going to only talk about scheduling and memory management here, but I’ll also go over the basics before getting into the details: how I simulated the CPU.

Tom Scott actually made an interesting video on what happens when the CPU actually runs the process:

The project, source code, and more details of the project are viewable via this Github link.

Intro

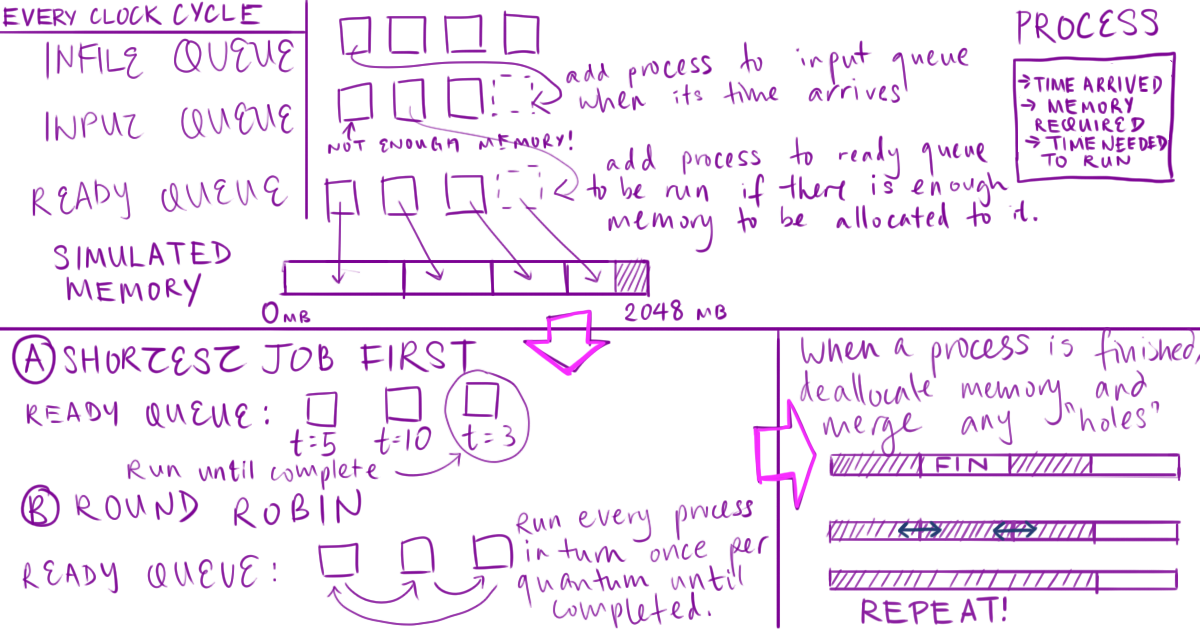

Firstly this assumes the simulation runs on one CPU, so only one process runs at a time, and a total of 2048MB of memory available to processes.

A process manager runs in cycles. A cycle of instructions occurs after one quantum, which is a length of time.

Here are the contents of a process.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

typedef struct {

uint32_t time_arrived; // first process always has time-arrived to 0

char *process_name;

uint32_t service_time; // Total time required to run

int memory_requirement;

int time_ran; // Total time taken to run (may be higher than

// its service time because of the quantum)

int state; // Number to keep track of whether it has not yet arrived,

// or is ready to run, or is currently running

// or is finished running.

int wait_time; // Time spent in the input and ready queue waiting to be run.

} process_t;

Clock cycle

Every clock cycle, the following instructions are run in sequence:

If the current running process (if any) is completed, terminate and dealloate its memory.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

// if there is a running processes if (running_process) { // if the running process is finished if (is_process_finished(running_process)) { // calculate summary numbers /* ... */ // terminate program, move to finished state free_process(running_process); running_process = NULL; // Merge holes merge_memory_holes(memory); } }

Submit processes that have arrived from the infile queue to the input queue.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

// iterate through infile list node_t *curr = infile_q->head; node_t *next; while (curr) { next = curr->next; // add process to input queue if its time has come. if (curr->p->time_arrived <= simulated_time) { process_t *to_enq = dequeue_process(infile_q); enqueue_process(input_q, to_enq); (*num_processes)++; } curr = next; }

- If there is enough memory to hold a process in the input queue, move the process to the ready queue and allocate the required memory (see Simulating Memory below).

- Determine the process which runs in this cycle according to the selected scheduling algorithm.

- Shortest Job First: If no process is running, identify the shortest process in the ready queue and run the process.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

// if no running process and ready_q has process, schedule next ready process in the queue if (!running_process && !queue_is_empty(ready_q)) { node_t *to_free = dequeue_node(ready_q); running_process = to_free->p; free(to_free); print_running_process(simulated_time, running_process->process_name, process_remaining_time(running_process)); }

- Round Robin: Place the running process in the back of the ready queue (if any), and run the next process in the queue.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

if (!queue_is_empty(ready_q)) { node_t *to_free = dequeue_node(ready_q); // No running process, like start of the program or when there // is a gap between processes, then schedule the first available process. if (!running_process) { running_process = to_free->p; running_process->state = RUNNING; } // If there is a currently running process, switch it out for the next ready process else { // place running process in the back of the ready queue running_process->state = READY; enqueue_process(ready_q, running_process); // Run the next process in the ready queue running_process = to_free->p; running_process->state = RUNNING; } free(to_free); print_running_process(simulated_time, running_process->process_name, process_remaining_time(running_process)); }

- Shortest Job First: If no process is running, identify the shortest process in the ready queue and run the process.

Simulating Memory

I implemented simulated memory allocation and deallocation using a doubly linked list.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

typedef struct segment segment_t;

struct segment {

int mem_start; // starting

int mem_end; //

segment_t *next_s; // next memory segment

segment_t *prev_s; // previous memory segment

process_t *process; // process allocated to this segment

};

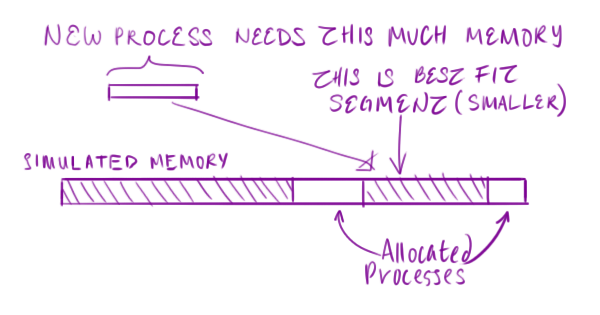

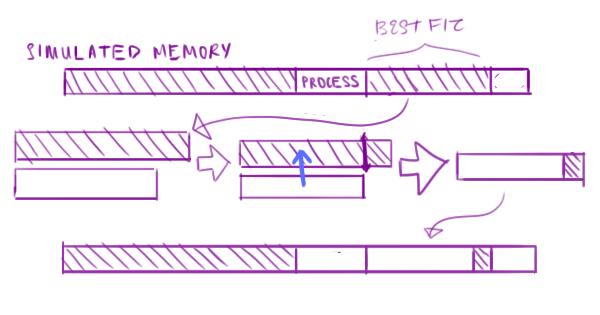

Allocation

Allocation:

Go through the simulated memory and find the smallest empty segment of memory that can be used by the next running process.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

segment_t *curr_segment = memory; segment_t *best_fit_segment = NULL; // Loop through all memory segments to find the best fit // for the current considered processes while(curr_segment) { // if current segment has a process, go to the next segment if (curr_segment->process != NULL) { continue; } // if the current segment can hold process in memory if (segment_available_memory(curr_segment) >= curr_q_node->p->memory_requirement) { // if there is no best_fit_segment, the current segment is best available if(!best_fit_segment) best_fit_segment = curr_segment; // get lowest segment's sequence number in case of equal size blocks else { if (segment_available_memory(best_fit_segment) > segment_available_memory(curr_segment)) { best_fit_segment = curr_segment; } } } // move on to next memory segment. Best fit searches all segments. curr_segment = curr_segment->next_s; }

If a best-fit segment has been found, split the segment so that it precisely fits the process’ required memory.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

// Split memory segment to accomodate process memory requirement int remaining_memory = best_fit_segment->mem_end - curr_q_node->p->memory_requirement; // assumes process memory requirement <= best fit segment size if (remaining_memory > 0) { // best_fit_segment reduces its size down to process->memory_requirement, and // the next segment will be inserted into linked list after best_fit_segment segment_t *next = make_new_segment(best_fit_segment->mem_start + curr_q_node->p->memory_requirement, best_fit_segment->mem_end); // insert in doubly linked list by changing pointers to their next and previous segments. best_fit_segment->mem_end = best_fit_segment->mem_start + curr_q_node->p->memory_requirement - 1; next->next_s = best_fit_segment->next_s; next->prev_s = best_fit_segment; // If best fit segment's next segment is not the end of the doubly linked list, // change *that* next segment's previous segment to point to the next segment above. if (best_fit_segment->next_s) { best_fit_segment->next_s->prev_s = next; } best_fit_segment->next_s = next; } // Finally, assign process to memory segment best_fit_segment->process = curr_q_node->p;

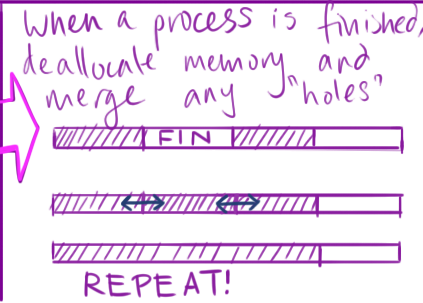

Deallocation

Deallocation:

- Remove the process from the segment of memory it used.

- Merge this now empty segment of memory with any adjacent empty segments.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

segment_t *curr = memory;

// Loop through all memory segments

while(curr) {

// Upon process finish, find the hole the recently finished process was in, or a hole

if (!curr->process || (curr->process && curr->process->state == FINISHED)) {

curr->process = NULL;

segment_t *nexthole = curr->next_s;

segment_t *to_free;

// Loop through potential next segments that are also holes

while(nexthole) {

if (nexthole->process && nexthole->process->state != FINISHED) break;

// merge nexthole into current segment

curr->mem_end = nexthole->mem_end;

curr->next_s = nexthole->next_s;

to_free = nexthole;

nexthole = nexthole->next_s;

free(to_free);

}

}

curr = curr->next_s;

}

Outro

And that is how a CPU manages processes. This is essentially what your computer does, except on a massive scale, and with multiple cores instead of one (running multiple processes at the same time, can cause issues with race conditions).